How To Write API Response Types with TypeScript

Developers of client applications work with APIs daily. It is a good practice to standardize API responses depending on the success of operations or business logic. Typically, a response includes standard fields such as status, error and etc.

With these standard fields, developers can react to the operation’s status and build further user interactions with the application. If the registration is successful, the form should be closed, and a success message should be displayed. However, validation errors should be shown in the form if the data is in the wrong format.

This raises the question of how to conveniently, quickly, and flexibly describe response types in a project.

The Problem I Encountered

Sometimes, response types in a project are described using just one type with many optional parameters. In most cases, this might be sufficient, and TypeScript will suggest these parameters when writing code, but additional checks for the presence of these parameters will be needed. Here’s an example of such a type:

export enum ApiStatus { OK = `ok`, ERROR = `error`, FORM_ERRORS = `form_errors`, REDIRECT = `redirect`,}export type ApiData = { status: ApiStatus error?: string errors?: Record<string, string> url?: string}The only advantage of this approach is its simplicity. We can add the ApiData type to any response type, and that will be enough.

export type UserProfile = { id: number name: string last_name: string birthday: string city: string}export type UserProfileResponse = ApiData & { user: UserProfile}// to simulate an API callconst updateProfileAPI = async(data: Partial<UserProfile>): Promise<UserProfileResponse> => { return Promise.resolve({} as UserProfileResponse)}However, I believe this single advantage is outweighed by a significant disadvantage. The downside of this approach is the lack of transparency.

Also, by adding such a type to response types, you never know exactly what the response for a specific request will be. Imagine that for a POST request, you can have a limited number of response scenarios from the API.

The scenarios might be the following ones:

- a successful operation with

status: 'ok'and some data - a validation error with

status: 'form_errors'anderrors: [{}, {}], and that’s it

It means you will never have the status: 'redirect' as a possible response scenario in this case. Also, why would you need a errors parameter for the response of GET requests?

It turns out that we cannot understand what exact response options we have just by looking at the response type. To understand all possible response variants, you need to open the code of the function that makes the request and processes the response.

Utility Types for Response Types

The disadvantages described above can be solved with the help of custom utility types. There is a separate type for each scenario: successful operation, server error, validation error or forced redirect.

These types can be used individually or combined to reflect all possible response options for a specific response. Each type will have a generic to allow for the type of data corresponding to that response to be passed in.

export enum ApiStatus { OK = `ok`, ERROR = `error`, FORM_ERRORS = `form_errors`, REDIRECT = `redirect`,}export type ApiSuccess<T extends Record<string, unknown> | unknown = unknown> = T & { status: ApiStatus.OK,}export type ApiError<T extends Record<string, unknown> = { error: string } > = T & { status: ApiStatus.ERROR,}export type ApiFormErrors<T extends Record<string, unknown> = { errors: Record<string, string> }> = T & { status: ApiStatus.FORM_ERRORS,}export type ApiRedirect<T extends Record<string, unknown> = { url: string }> = T & { status: ApiStatus.REDIRECT,}export type ApiResponse<T extends Record<string, unknown> | unknown = unknown, K extends Record<string, unknown> = { error: string }, R extends Record<string, unknown> = { errors: Record<string, string> }> = ApiSuccess<T> | ApiError<K> | ApiFormErrors<R>Additionally, I created the general ApiRespinse type, which includes several utility types. It will save time for adding all scenarios for each POST request.

Here are examples of using these utility types for different scenarios:

export type FetchUserProfile = ApiSuccess<{ user: UserProfile}>export type FetchUserConfig = ApiSuccess<{ config: Record<string, string | number | boolean>}> | ApiErrorexport type AddUserSocialNetworkAsLoginMethod = ApiResponse<{ social_network: string, is_active: boolean}, { message: string }> | ApiRedirect<{ redirect_url: string }>Practical Difference

Below is an example of types for the user profile and the response returned by the user profile update function.

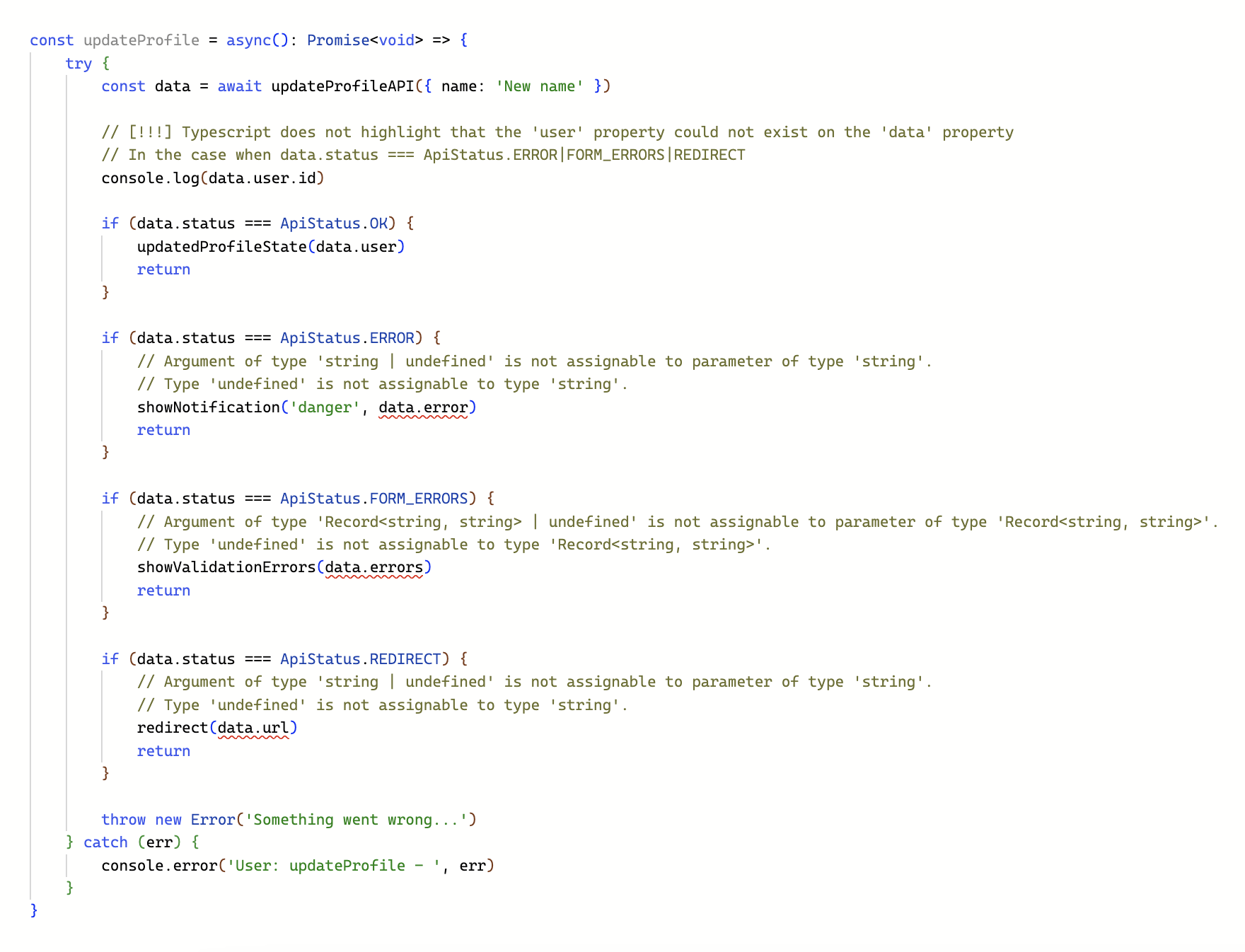

const updateProfile = async(): Promise<void> => { try { const data = await updateProfileAPI({ name: 'New name' }) // [!!!] Typescript does not highlight that the 'user' property could not exist on the 'data' property // In the case when data.status === ApiStatus.ERROR|FORM_ERRORS|REDIRECT console.log(data.user.id) if (data.status === ApiStatus.OK) { updatedProfileState(data.user) return } if (data.status === ApiStatus.ERROR) { // Argument of type 'string | undefined' is not assignable to parameter of type 'string'. // Type 'undefined' is not assignable to type 'string'. showNotification('danger', data.error) return } if (data.status === ApiStatus.FORM_ERRORS) { // Argument of type 'Record<string, string> | undefined' is not assignable to parameter of type 'Record<string, string>'. // Type 'undefined' is not assignable to type 'Record<string, string>'. showValidationErrors(data.errors) return } if (data.status === ApiStatus.REDIRECT) { // Argument of type 'string | undefined' is not assignable to parameter of type 'string'. // Type 'undefined' is not assignable to type 'string'. redirect(data.url) return } throw new Error('Something went wrong...') } catch (err) { console.error('User: updateProfile - ', err) }}Here is an image of how TypeScript lint this code:

In the image, you can see some expected values for standard responses, such as error, errors, or url, are highlighted by TypeScript. This is because the linter considers that these values might be undefined. This is easily resolved with an additional check along with the status, but it already shows the problem with this approach.

Also, note that in the line with console.log(data.user.id), the value user is not highlighted as potentially undefined. This is how it will be if we receive any response type other than a successful one.

...

Using utility types such as ApiResponse and others, we won’t have such problems.

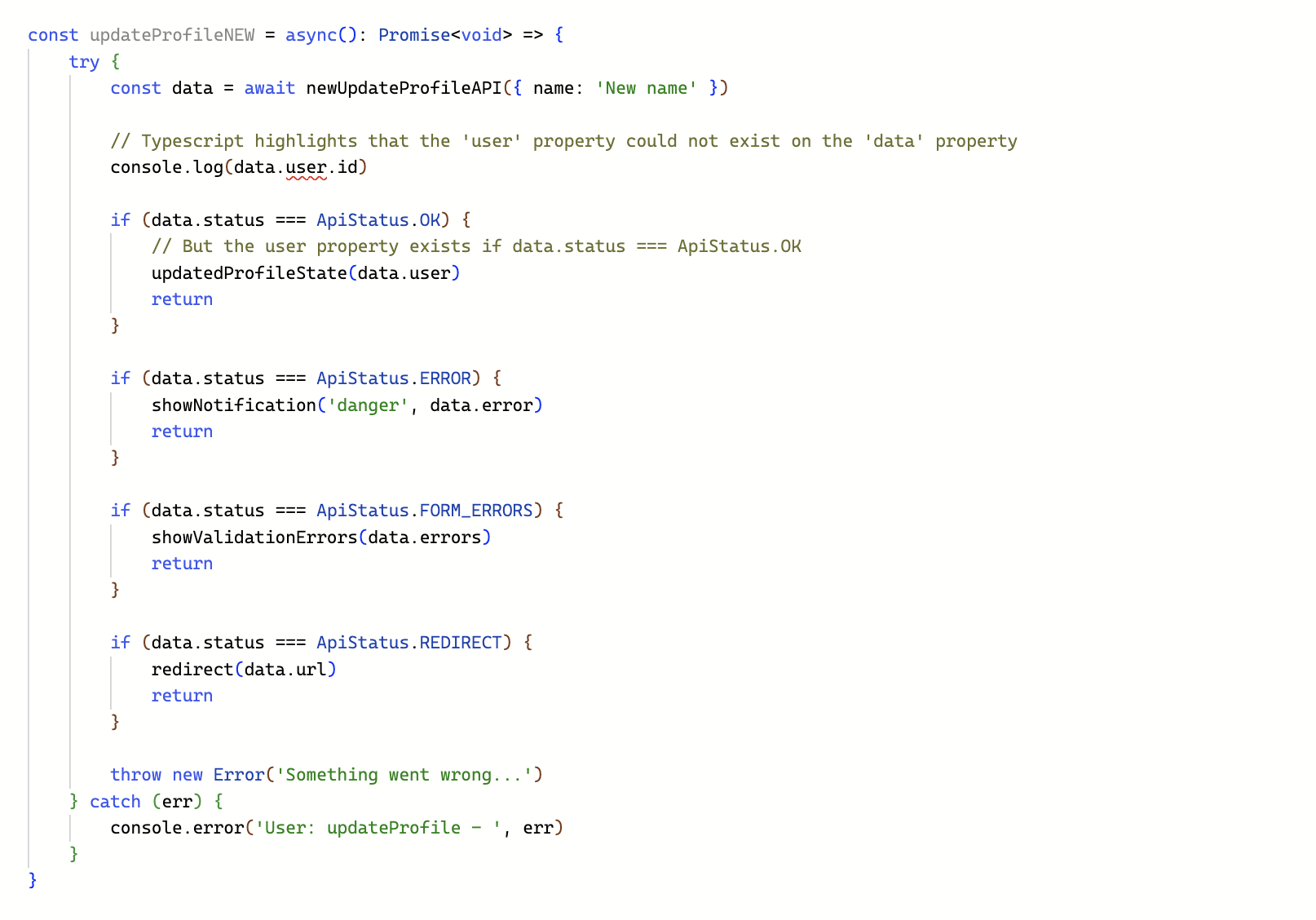

export type UserProfileResponseV2 = ApiResponse<{ user: UserProfile}> | ApiRedirectconst newUpdateProfileAPI = async(data: Partial<UserProfile>): Promise<UserProfileResponseV2> => { return Promise.resolve({} as UserProfileResponseV2)}Here is an image of how TypeScript lint this code:

In this case, everything works as expected:

- TypeScript understands that for corresponding statuses, there will be corresponding standard fields.

- It indicates that the

uservalue might beundefinedin all response types except the successful one. However, after checking the response's success, this value is not highlighted and is defined.

Conclusion

After implementing these utility types in the project, the developer experience was significantly improved. Now, the types fully correspond to the possible response scenarios that the API can provide.

This will also help avoid potential errors where some values might be used that are unavailable in certain response types, as in the example with the user value.

Additionally, there is no need to look at the response processing implementation in the code to understand the real response types. You can immediately see the complete picture.

...

If you are interested, you can take a look at how it works on the Typescript Playground page.